Routes into the Environment

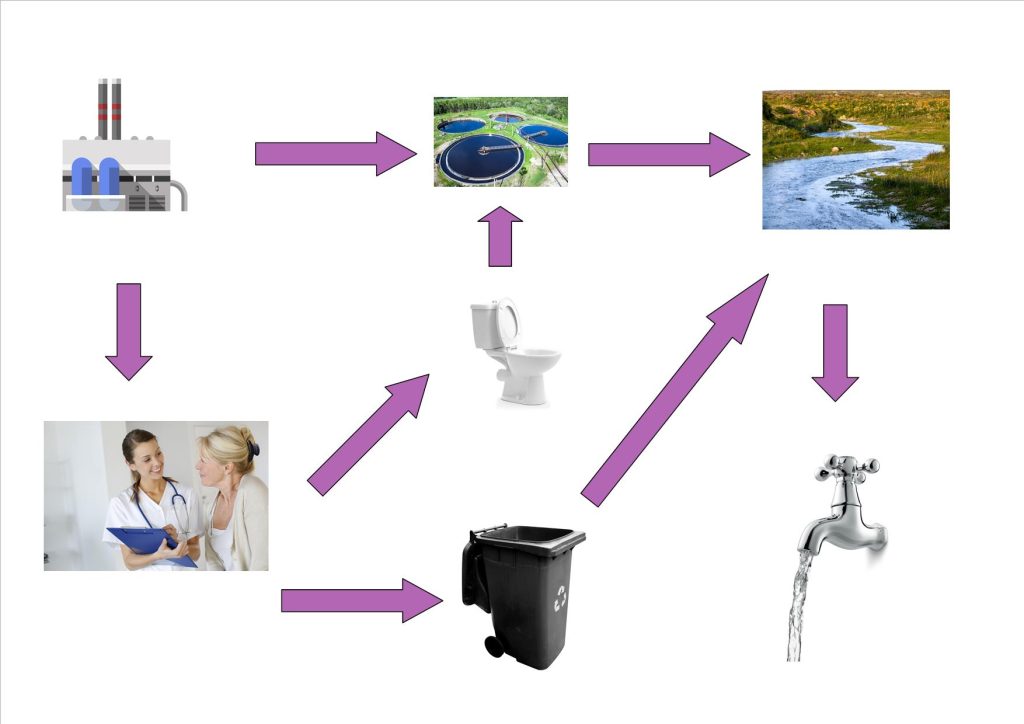

There are three main routes by which pharmaceutical molecules enter the environment, which are shown in Figure 1:

- Normal patient use;

- Improper disposal of unwanted pharmaceuticals and related medical devices such as patches, implants etc. into landfill or water courses;

- Point source pollution at sites of manufacture/formulation.

A fourth route which is starting to become more prevalent (or at least better detected) is the illegal or off-label use of pharmaceuticals resulting in accumulation in unintended species such as plants and animals.

Normal patient use

Improper disposal

Improper disposal of unwanted or unused pharmaceuticals occurs via direct flushing of products into the municipal sewage system or via municipal solid waste systems, which are usually destined for landfill. Eventually APIs in landfill sites may leach out and contaminate ground water, although if blister packed or in containers, these would have to degrade first. Controlled landfill sites should collect leachate, therefore limiting this route to the environment – however, legislation governing this varies worldwide. Other solids like syringes, implants and patches improperly disposed of in landfill could also lead to API contamination of groundwater. Other improper disposal routes include the illegal landfilling or dumping into water courses of industrial waste containing API residues to avoid costs associated with proper disposal routes (land fill tax, incineration).[1] As an example, over 1,000 tonnes of unused or unwanted pharmaceuticals disposed of in Sweden in 2011. Whilst the majority (around 800 tonnes) were disposed of correctly through patient return or recycling stations, around 250 tonnes were still disposed of through home disposal.[2]

Unused medicines arise from a wide range of factors: patients not completing the prescribed course, failure to take due to undesirable side effects, out of date drugs, damaged packaging, and many others. It is debatable as to the extent of the escape of APIs into the environment via this route compared to normal patient use and point source pollution.[3]

- S. Castensson and A. Ekedahl, Pharmaceutical Waste: The Patient Role, Green and Sustainable Pharmacy, 2010, 179-200.

- Measures to reduce disposal of pharmaceuticals in distribution and health care (Last accessed: August 2022).

- C. G. Daughton and I. S. Ruhoy, Environmental footprint of pharmaceuticals: The significance of factors beyond direct excretion to sewers, Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry, 2009, 28, 2495-2521.

- Examining the Life Cycle

- Drivers Towards Whole-process Thinking

- Challenges in Effecting Change

- LCA Examples

- Primary Manufacturing

- Secondary Manufacturing

- Packaging

- Pharmaceuticals in the Environment (PIE)

- Appendix: Carbon Footprinting Assumptions

- Examining the Life Cycle: Quiz

- Examining the Life Cycle: Summary and Further Reading

- The Fate of APIs

- Benign by Design

- Life Cycle Impacts: Summary and Further Reading