Bio-derived Solvents

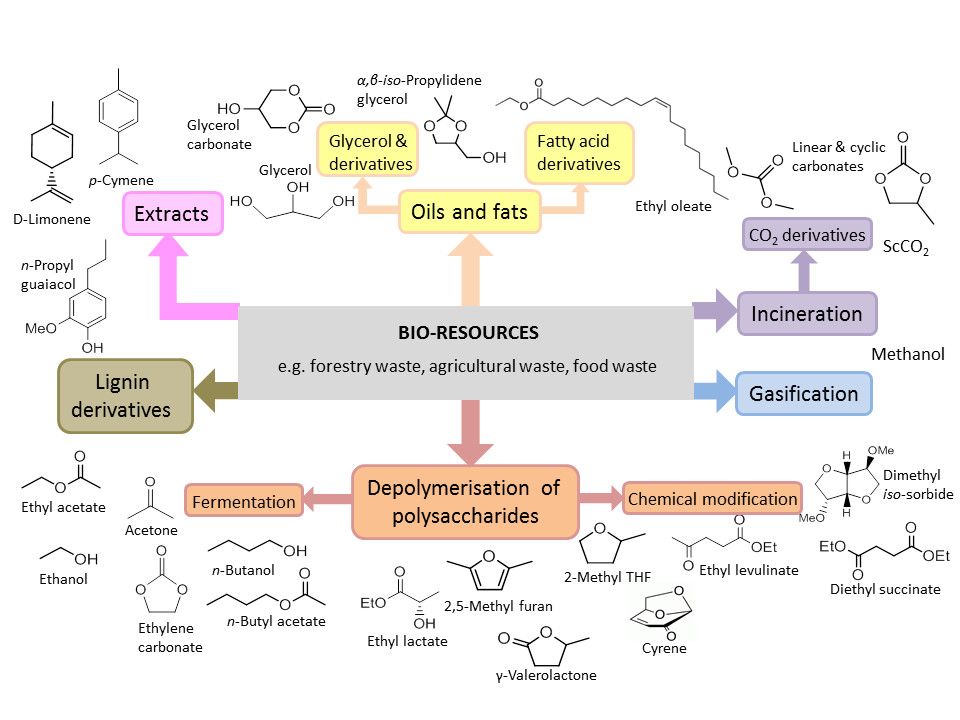

As was discussed in the Renewable Resources module, there is a drive towards the manufacture of bio-based chemicals and a number of bio-derived solvents are now readily available. Although bio-derived solvents are not always safe and non-toxic, as they are renewable, they reduce concerns about the use of finite resources such as oil and natural gas.[1] Typical examples of bio-derived solvents include bio-ethanol, limonene and 2-methyl tetrahydrofuran (2-MeTHF). Bio-derived solvents may be renewably derived replacements to established solvents or novel molecules such as dihydrolevoglucosenone, a bio-based alternative for dipolar aprotic solvents.[2] A broad range of bio-derived solvents will be required to reduce dependence upon traditional fossil derived solvents. Figure 1 shows a range of possible solvents that can be derived from bio-resources such as forestry, agricultural and food wastes.

Figure 1: Some examples of bio-derived solvents

It cannot be assumed that simply because solvent is bio-derived, it is automatically green. The CHEM21 Solvent Selection Guide assesses newer bio-derivable solvents alongside traditional solvents.[3]

One consideration in the case of some bio-derived solvents is their greater viscosity and higher boiling points, which can lead to potential issues with recycling and recovery due to higher energy demands.[4] Whether or not this presents an issue depends upon the industrial application of the solvent.

Recommended reading:

J. H. Clark, A. J. Hunt, L. Moity and J. Sherwood, Renewable Solvent Selection in Medicinal Chemistry, in Green and Sustainable Medicinal Chemistry: Methods, Tools and Strategies for the 21st Century Pharmaceutical Industry, L. Summerton, H. F. Sneddon, L. C. Jones and J. H. Clark, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK, 2016, ch. 3, pp. 28-40.

G. Paggiola, A. J. Hunt, J. McElroy Con R and Sherwood and J. H. Clark, Biocatalysis in bio-derived solvents: an improved approach for medium optimisation, Green Chem., 2014, 16, 2107–2110.

- J. H. Clark, A. J. Hunt, L. Moity and J. Sherwood, Renewable Solvent Selection in Medicinal Chemistry, in Green and Sustainable Medicinal Chemistry: Methods, Tools and Strategies for the 21st Century Pharmaceutical Industry, L. Summerton, H. F. Sneddon, L. C. Jones & J. H. Clark, Royal Society of Chemistry, Cambridge, UK, 2016, ch. 3, pp. 28-40.

- J. Sherwood, M. De bruyn, L. Constantinou Andri and Moity, C. Rob McElroy, T. Farmer Thomas J and Duncan, W. Raverty, A. J. Hunt and J. H. Clark, Dihydrolevoglucosenone (Cyrene) as a bio-based alternative for dipolar aprotic solvents, Chem. Commun., 2014, 50, 9650–9652.

- D. Prat, A. Wells, J. Hayler, Sneddon, C. R. McElroy, S. Abou-Shehada and P. J. Dunn, CHEM21 selection guide of classical- and less classical-solvents, Green Chem., 2016, 18, 288–296.

- C. P. Ashcroft, P. J. Dunn and A. S. Hayler John D and Wells, Survey of Solvent Usage in Papers Published in Organic Process Research & Development 1997–2012, Org. Process Res. Dev., 2015, 19, 740–747.